Now that I have returned to my alma mater Towson University as an instructor, I decided to dig through my old filing cabinet in the basement and look at some of my work there as a student. And, since I am always looking for something to blog about, I have decided to share it with you. (Pray I don't start posting blogs about my grade school work!)

This is last of three short stories I wrote for a fiction writing class taught by Dr. Carl Behm in the fall semester of 1982. The class was in the English Department. Since my schedule never allowed me to the take the screenwriting class in my Mass Communications major, these were my only true fiction writing assignments at the University. In retrospect, I wish I had taken more writing classes. At the time I needed the discipline of a class deadline to finish a project. Most of my juvenile writings were left uncompleted.

I forgot the specific parameters of this short assignment. Most of my fellow students wrote thoughtful, introspective pieces. Navel gazing, some might say. Not me. My stories tended to be heavily plotted. Not that they weren't personal. They were, but in a very submerged manner.

Up until this year, my writing had been mainly comic. All three of the stories I wrote in this class were darker than anything I had previously attempted. Why? Because I had recently broken up with my long time girlfriend and I was spiraling downward emotionally. My ex, who remained a friend, read the stories and became concerned. She thought I was suicidal. I told her I wasn't, but she saw things more clearly than I did.

Enough ado. Here's my last story for the class. Although I corrected a few grammatical errors, I resisted the urge to truly rewrite or correct the piece. I wanted this to reflect my viewpoint and talents at the time.

I forgot the specific parameters of this short assignment. Most of my fellow students wrote thoughtful, introspective pieces. Navel gazing, some might say. Not me. My stories tended to be heavily plotted. Not that they weren't personal. They were, but in a very submerged manner.

Up until this year, my writing had been mainly comic. All three of the stories I wrote in this class were darker than anything I had previously attempted. Why? Because I had recently broken up with my long time girlfriend and I was spiraling downward emotionally. My ex, who remained a friend, read the stories and became concerned. She thought I was suicidal. I told her I wasn't, but she saw things more clearly than I did.

Enough ado. Here's my last story for the class. Although I corrected a few grammatical errors, I resisted the urge to truly rewrite or correct the piece. I wanted this to reflect my viewpoint and talents at the time.

CHRISTMAS

I haven't hung a Christmas decoration in over sixty years.

Once I spat in the collection bucket of a Salvation Army Santa Claus in Chicago. I'm not really proud of that. I was drunk. But I like to tell people about it just to raise some eyebrows. It certainly raised Santa's eyebrows. I thought he was going to punch me. That sure as hell would have been a pleasant spectacle for the evening shoppers.

Let me tell you a nice Christmas story. A true one. That's what the story of my life is. Maybe you'll find it interesting. Maybe you'll learn something. I really don't care. Maybe I'm a cynical old bastard, but there is one thing that I know for sure. A person doesn't live as long as I have without learning a thing or two.

I was born in Canada. Things were a lot different in Canada than they are now. Back in the eighteen-nineties, it wasn't even a truly independent country. We were part of the British Empire and damned proud of it. I know it is still part of the Commonwealth, or whatever, but it was different when I was growing up. It really meant something to be part of the Empire. Hell, the Empire was half the damned world. It was the biggest and richest Empire in the history of the world. The old saying was true: the sun never set on the British Empire.

Sure, the United States is a superpower now, but it couldn't compare to the British Empire of my youth. England, Canada, Australia, India, half of Africa and countless islands and subject nations all united under one language and moral code. It was enough to make a person's head swim. I bought it hook, line and sinker. We didn't have the term master race back then, but we considered it obvious that it was us. Anglo-Saxons were the natural rulers of the world. We didn't have to talk about it. It was obvious. Any fool could see that.

It wasn't surprising that I joined the British army when I came of age. I joined a Canadian regiment, the 104 Canadian Light Infantry. My family was all for it. They probably would have pressured me into joining if I wasn't an enthusiastic recruit. My father was a native of London and he joined the army when he was a young man. He traveled all over the world before he settled in Canada when he retired. He felt all men should join the British army. It would give them a chance to see the world while it made you a man. I was all for it.

I loved the army. It was everything I hoped it would be. I loved the tradition, the pride and the code of honor. I even rose to the rank of Corporal before the Great War. My family was so proud of me because it was difficult for a man without connections to be promoted during peacetime. My father was in the army for over twenty years and ended his career as a master sergeant. He received his promotions during various "adventures." He said if I was lucky, war would break out and I might have a chance to actually rise in rank. And believe me, my father wasn't the only one who wanted war.

The storm was brewing. During the three years that I was in the army before the outbreak of war, even when I was stationed in India, you could sense that a big war was coming. I don't think anyone could have guessed what the spark would be, but we knew the fuse was primed. Early in 1913, our regiment was stationed in England. We were excited. When the war broke out, we would be one of the first to fight. It wouldn't be long, we knew that. The Germans had been asking for war for years. I couldn't wait for the opportunity to put them in their place.

It came in August of 1914. When the news got to our regiment that war had been declared, we cheered. Everyone was cheering. Church bells were ringing. The whole damned nation was cheering. We had a hell of a celebration in the barracks that night. The great adventure, the great crusade, was on. Now we would get the chance to show the world what were were made of. We never doubted the eventual triumph of our values and virtues. I expected the war to be the best six or seven months of my life. I didn't think it would take any longer that that.

Just as I hoped, our regiment was one of the first units to cross the channel. We were part of the British Expeditionary Force under the command of General French. By the time we first saw action, the Germans had pushed the French and Belgians back. Things weren't going well, but that didn't bother me. I knew the situation would change once we reached the front.

We were also pushed back in the first couple of skirmishes we were engaged in. I didn't lose hope. I could see that had bloodied the Germans badly each time we clashed. I firmly believed that when the rest of the British army arrived in France, we would teach the Germans a thing or two.

Meanwhile, we were losing a lot of men. I would guess that we lost a third of the men in the regiment before the first battle of the Marne. I maintained my stiff upper lip. All soldiers know that some of us will never go home. You just had to believe that cause was worth the sacrifice. I was willing to die for my values, the values of my civilization. I never doubted it.

After the Marne the situation changed. We were the ones who doing the pushing. Casualties were high but the end was in sight. I thought we only needed one more big victory to end the war. It was great! This was everything that I wanted out of the war -- the sense of victory and glory. To see our army beating back the barbarians filled me with an unbelievable sense of patriotism and pride.

We pushed and pushed until we came to a village called Amas. The Germans could not be pushed beyond that point. I didn't know it then, but our regiment would never be more than four miles from that spot for the next three years. This is where the real hell began.

We tried again and again to dislodge them from their defensive positions on a low ridge. Finally, we were forced to set up a defensive position on a low ridge a couple hundred yards back from the Germans. This is how tench warfare began, and it was horrible. Enemy sniping kept you practically stooped over all the time. Our noses were always filled with the stench of hundreds of unrecovered, decaying corpses strewn about in no man's land between our lines. Rain would make mud up to your knees in the trenches. You could get used to the constant shelling, but there was no getting used to the bayonet charges.

When I was a raw recruit, I believed the bayonet charge was the most glorious sight on Earth. Seeing a whole regiment of men charging in unison, shouting glorious old calls was certainly impressive on the parade ground. On the battlefield, killing with a bayonet is a mean, horrible job. But killing with a bayonet couldn't compare to the terror you felt when you saw the Germans charging your positions with bayonets fixed. The worst moment was the split second when you realized that you would have to stop shooting and prepare for hand-to-hand combat. That moment always came no matter how many of them you killed with the machine guns. Some would always get through. It still sends shivers down my spine when I think about it.

It was an ugly business, but I did it. It was a job that had to be done. The cause was worth the sacrifice. Our losses were incredibly heavy. By the end of November, our regiment was down to a quarter of our original strength. I had been promoted to sergeant. Our original sergeant was killed when he stayed behind to give us cover as we returned from a foray against the enemy. We were not in a position to retrieve his body and it remained unburied in no man's land for weeks. The body was so close to our lines that I could see his still open eyes staring lifelessly at us until they blackened. That was an image that still haunts me. He was a good man, and, more importantly, a good soldier. Honor itself dictated that he deserved a Christian burial.

I was promoted in late November. For a few weeks, the front quieted down. We really couldn't attack. We were too low on men. We were waiting for reinforcements, and I guess the Germans were as well. In early December our reinforcements began to arrive. They were a bunch of farm boys from Canada who seemed to bring the cold northern wind with them. They were young, patriotic volunteers, but the only training they received was on the ship from Canada. They couldn't wait to fight and got their chance right away. We tried to overrun the forward German trenches. The results were the same as usual. We pushed them out, but we got pushed back when their reserves attacked. We got back to our lines minus fifty-seven men. Little did I know the effect one of them would have me.

I can't remember the kid's name. I probably never even knew it. He was one of those big farm boys that had just joined the regiment. He was hit on the way back to our lines after the attack. I didn't know he was still alive until the shooting died down. Then we could hear him crying for help. He must have been hit in the spine since he was paralyzed from the neck down. He couldn't move, but he could yell and that was exactly what he did.

As you can imagine, his constant pleas drove us crazy, especially the new men. Some of them volunteered to rescue him, but I refused. My orders prevented me from making any major foray into no man's land, and I couldn't send out a small group. The Germans would kill them for sure. They could hear the wounded man too. If they wanted, they could easily kill him, but they didn't. They kept him alive so that he would lure out a rescue party. It was a nasty trick, and I wasn't going to let any of my men fall for it. I just hoped the poor man would die during the night, and put us all out of our misery.

He was still alive when I woke the next morning. All of the men in my area were on edge. The veterans were all cursing the Germans for not killing him, and the new recruits wanted to rescue him. I explained the situation, but they still wanted to act. They argued it was the honorable thing to do, and it was our honor that separated us from the Huns. Still, I said no. I wouldn't let them commit suicide.

The next night the kid was still hanging on somehow, though his cries had grown fainter. Looking back, I should have put some hardened veterans on guard duty that night. Six of the new guys went over the top around midnight. I didn't hear anything. You learn to be a sound sleeper when you get shelled most nights. But the Germans heard them. They dropped a flare on them and machine gunned them before they got to the wounded kid. They pointedly did not fire on the kid, who remained alive and moaning.

That was it. Six men were dead. I couldn't allow this to go on much longer. I hoped that he would die during the day. If not, I would have to do something I never imagined myself doing. Well, he didn't die.

I waited until it was late, around eleven o'clock. As I stood looking over the top of the trench, I quietly attempted to locate where the wounded man laid. Luckily, he began to softly cry. I could sense his exact location. I got my rifle and took aim.

I squeezed off the first shot. It was followed by a faint cry of pain. Despite myself, I smiled. It had been a tough shot. I adjusted my aim slightly and fired again. That shot killed the kid. He never made another noise.

Everyone knew I killed him, but no one reported me. I got a lot of dirty looks from new recruits, but the veterans respected my decision. They knew someone had to do it. If anything, some of them reasoned, I had put him out of his misery. Still, no justification, no matter how logically accurate, made me feel any better. I felt worthless, as if all of my honor and virtue had been stripped away. In my pre-war mindset, it would have been perfectly honorable for the kid to kill himself, or for me to die trying to rescue him. Killing him like this, however, felt like murder. I was no better than a German.

Things quieted down until about two weeks before Christmas. That's when we began our Christmas offensive. Rumors spread like wildfire that there was going to be a Christmas ceasefire, but the generals wanted a victory before that. They wanted a victory to cheer up the folks at home for the holidays, and they didn't care how many young died to achieve it.

We got our orders and did what we had to do. I didn't care anymore. I was just going through the motions. The war had lost all meaning to me. It isn't like I didn't fight. I fought as hard as I could. This campaign was definitely the bloodiest, see-sawing engagement I had experienced up to that time. The battle slowly ground to a halt the day before Christmas with us ending up pretty much where we started, but with half the men. We needed the truce. The Germans could have overrun us easily, if they had the strength to attack. However, I think they were as badly cut up as we were.

I will never forget that Christmas Eve. Even a few minutes before midnight, we fell under a terrible artillery barrage. It was as if both sides had quotas to fill before the truce. Actually, we did not know whether there was really going to be a ceasefire or not. We were instructed not to initiate any small arms fire after midnight unless fired upon, but we didn't know what was going to happen.

A few minutes before midnight, no was was asleep and no one was talking. All of the men in my bunker were watching me, and I was watching my watch. As the seconds of the last minute ticked away, the intensity of the shelling decreased rapidly. By the time the second hand reach the twelve, an unnatural silence fell across the front as far as I could hear. Everyone in my bunker held their breath. I looked up to the remnants of my unit and said, "Merry Christmas." The men started to cheer, as men everywhere up and down the line did. I left the celebration and walked out to the trenches. I told the sentries to make sure that they didn't fire unless they were actually fired upon. After that, I went to my bunk and fell right to sleep.

I was up at dawn the next morning. It was so quiet. Other than some men singing Christmas carols, there was no noise. Most of the men were still asleep. This was the latest most of them had slept in weeks. I was willing to let them continue to do so, but I received different orders. I had to get all of the men up, leave a skeleton guard, and take the rest of them back to an open field about a mile behind our lines for a divisional Christmas service.

I got the men up with no complaints. Hell, I think I could have marched them thirty miles without any grumbling. Nothing could break the mood of peace and cheerfulness. I have to admit it, I was catching it, too. This unofficial truce brought back feelings I hadn't allowed myself since I killed the wounded kid. The ceasefire proved we were more than just animals. This truce was a tribute to everything and civilized in the world. I was surprised that our leaders could get the Germans to agree to it.

After the services, we had the best breakfast we had in months, eggs, bacon, wheatcakes laden with syrup and coffee. I was called away early for a regimental meeting where we received orders for the rest of Christmas day.

Once we got back to our lines, we were to retrieve as many of the bodies as possible from no man's land. Our officers told us the Germans were already doing the same thing. We were warned not to carry weapons into no man's land and not to make any threatening moves like wandering too close to their lines. After we retrieved the bodies, we were to allow the men to relax and entertain themselves. That evening we would also receive a special meal.

When we got back to our lines, we laid planks over the trenches so that we could roll wagons into no man's land. I briefed the men on the situation. I told them not to go any further than halfway toward the German lines. I wasn't taking any chances.

We began collecting the bodies. It's hard for me to describe the joy I felt despite the inherent gruesomeness of the job. Most of the bodies were mere fragments, blown apart repeatedly by artillery shells. Other bodies laid in a crumbling state of decomposition. Still, it felt like a victory. Those men were heroes and there bodies had laid out in the open like rubbish. Now we were finally able to treat them with the respect they deserved. It was another victory of our Christian virtues. I found myself believing in the cause again.

It wasn't long before we made contact with the enemy. There were a lot of German bodies on our side of no man's land, and a lot of our bodies on their side. My men came and asked me what to do with all of the German bodies. I went to the Captain and he told me to carry the German bodies to the middle of no man's land so that the Germans could take care of them.

When we started stacking the German bodies, they responded by stacking our bodies in the middle of no man's land as well. Eventually, they were crossing the middle to retrieve bodies, and we were doing the same. However, our men never strayed near their trenches and they didn't approach ours. I was a little wary at first, but I grew confident that the Germans would respect the cease-fire.

In two hours, our sector was cleared of corpses and I told the men they could relax. The weather was exceptionally mild and most of the men sat around in small groups near our positions in no man's land just enjoying the peace. I saw smiles on the faces of my men. For some of the replacements, this was the first time I ever saw them smile. I just sat alone and watched them. It felt good, really good.

Around three o'clock, one of my men brought out a football, or soccer ball as we say in this country now. I don't know where he got it. He must have had it hidden away the whole time he was in France. I found it odd, but I shouldn't have been surprised. It's amazing what people bring to war. Some people bring Bibles. Others bring soccer balls. To each his own. All I brought was my rifle and my ideals. The rifle was holding up better, but my ideals still lingered on that day.

The game attracted a lot of attention. It wasn't long before most of the men in the regiment were on the sidelines cheering and placing bets. The game attracted the attention of the Germans too. A few of them began drifting closer and closer. The Germans were unarmed, but I went down to the game to make sure there was no trouble.

The men were only playing to four and the game was quickly over. When it ended, many men volunteered to play a second game. When they were picking teams, a handful of Germans approached. In halting English, one of them challenged my men to a game.

Ashworth, the private who owned the ball, ran to ask my permission. He was obviously keen on the idea. I looked at the Germans. They seemed sincere enough. Nothing indicated that this was a prelude to a sneak attack. I turned back to Ashworth and asked if he really wanted to play them. He said yes. He wanted to beat them.

So it was up to me.

As you can imagine, it was quite a decision to make. Technically speaking, I shouldn't have been the one to make it. I should have run it up the chain of command. That was the safest thing to do for both the men and my career. However, it was Christmas and everyone wanted to do it. Who was I to say no after the unremitting hell we had experienced over the last few months?

I warned Ashworth that there better not be any rough stuff. He said he wouldn't start anything. Then I walked over to the German who could speak English. I told them that they could play as long as the game didn't get out of hand. He assured me that they would keep the game friendly. I gave my approval and a cheer went up.

My men huddled and picked a team. I was surprised to learn that their were men in the unit who played at the University level. I smiled. It certainly appeared we would make quicker work of the Germans on the football field than we had on the battlefield.

Word of the game spread before the teams were even selected. Men, from both sides, started showing up from the entire sector. British and German soldiers worked together to clear the debris from a sufficiently flat area in no man's land to create a regulation field.

As I watched, I feared that things were already getting out of hand in a way I didn't anticipate. My own immediate superiors watched from the trenches. They obviously didn't disapprove, or they would have put an end to it, but they wanted to keep their distance in case things went bad. And it looked like it might. Suddenly, the men around me began to drift away. I saw why. The Captain and his staff were approaching. He wanted to know how I could be so insane as approve the game. I asked if he wanted me to cancel it but he said no. It was too late now. However, he made it perfectly clear I would receive the blame if anything happened.

The game was to be played according to international rules. One of my men, a former University player, acted as referee. My worst fears were allayed after a couple of minutes. Both teams played hard. Each of them obviously wanted to win. But no one wanted to ruin this strange, magical moment with unsportsmanlike conduct. I felt extremely proud that my men possessed a sense of honor that permitted them to put aside their justified antipathy toward the Germans to play a regulation game. I was surprised that the Germans were able to do the same.

As I lit up a cigarette, I heard someone walking toward me from behind. I looked over my shoulder and saw a German officer approaching. He was their equivalent of a lieutenant. Feeling generous, I held up my packet of cigarettes. He smiled and nodded. I took one out and handed it to him. He thanked me in very good English, American English actually.

We introduced ourselves as we watched the game. His name was Joseph Engel. I complimented him on his English. He told me he had lived for a few years in America. He worked for an uncle who owned a prosperous import/export business based in Philadelphia. The year before the war, his uncle transferred him to his Hamburg office. When the war came, he enlisted. "I only thought it would be for a few months," he said with a smile.

I told him my life story. He was surprised to hear I was Canadian. He asked why I had joined the British Army. I told him the Canadian army was small and didn't offer the excitement and opportunity I sought. He said he understood, but I don't think he did. How could he? How could a German understand the sense of pride one got in being a soldier in the British Army. He was just being friendly.

I was beginning to like the guy.

We turned our attention back to the game. It was strange. There were no serious incidents. The players were being unusually courteous. The fans quieted down, too. Their eyes remained glued on the action, but the cheering subsided. There was still tension, but there was also a profound sense of peace. The game brought about a strange unity. I looked to Engel, my enemy friend. He didn't say anything. He didn't have to. I knew he could feel it too.

The game ended with the Germans winning by one point. Both sides applauded the winners. That surprised me. As the applause died, the Captain ordered our men back to our lines. They were hesitant, as if they didn't want to break the spell. At around the same time, German officers began to send their men back to their positions.

I had to go. I turned to Engel but I couldn't say anything. He broke the silence. He said it was a great pity we would never meet again. Suddenly an idea popped into my head. I told him that we could meet after the war. He smiled, after all, that the was oldest lie soldiers shared. But I meant it, and he could tell. He said he would like too. We talked a little before we decided on a time and place. We agreed to meet in Boston on Christmas day, one year after the end of the war. We would meet at six o'clock in the evening in front of City Hall. It was set. We wished each other the best of luck and we both hoped that it would not be too long before we met again.

It wasn't.

Christmas ended at midnight and so did all of the delusions of peace. Shelling began seconds after midnight. It wasn't particularly heavy, but it was enough to force us to keep our heads down. The war was back. It was a terrible feeling.

The next morning the commanders in my regiment were called to together. We were ordered to attack. I couldn't believe it. A major assault the day after Christmas? They were insane. The generals felt an attack was necessary because our forces were in a weakened state and couldn't withstand a heavy German assault. They said we had to attack preemptively to throw the Germans off balance.

We went over the top after our forces shelled the German positions mercilessly. It was a typical bayonet charge. At first my heart wasn't in it, but the professional soldier in me took over.

As was normally the case when we pit bayonets against machine guns, we lost a lot of men charging across the field, but we didn't stop. I charged blindly, leading the men on. We hit their line like a bulldozer, forcing the Germans out of their trenches into a fighting withdrawal. We continued to push them.

I bayoneted a German private who turned to challenge me. As I pulled the metal out of his ribcage, one of my men fell to the ground next to me. I turned to the man who had shot him and charged in blind rage.

My eyes focused on my target. It was Engel. He faced me with his pistol in hand. He recognized me at the same time. In a moment of weakness or friendship, he turned the barrel away from me. I wanted to stop too, but I couldn't. I drove the bayonet deep into his chest then pulled it out. Engel closed his eyes and fell backwards.

I stood over his body. I don't know why but I began to drive my bayonet into his lifeless body again and again. I don't know how many times I did it. When I stopped, I threw my rifle to the ground and pulled Engel's pistol from his hand. I closed my eyes, opened my mouth and pointed the barrel of the gun to the roof of my mouth. I pulled the trigger but nothing happened. The pistol was out of ammunition.

I hate Christmas.

Rereading this piece, I can see why my ex-girlfriend thought I was suicidal. Dr. Behm liked it. He also appreciated that I attempted a historical piece. He said not many students attempted that.

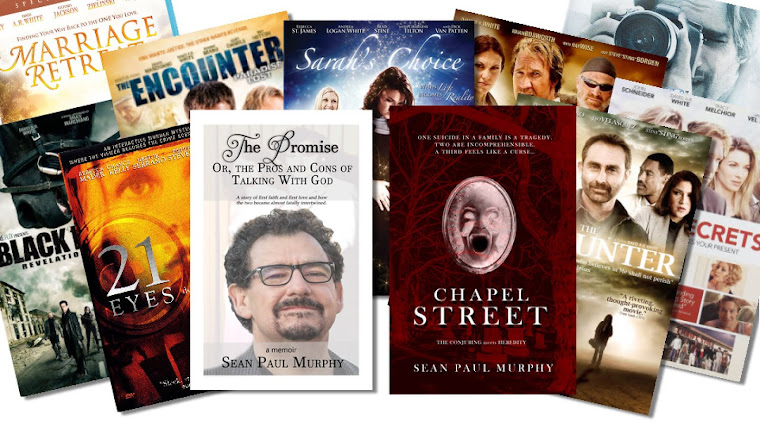

If you want to see if my writing has improved since college, you should check out these sample chapters of my novel Chapel Street, which will be published by TouchPoint Press in July of 2020.

Sample Chapters:

Prologue - My Mother

Chapter 1 - RestingPlace.com

Chapter 2 - Elisabetta

Chapter 3 - The Upload

Chapter 4 - The Kobayashi Maru

Chapter 5 - Gina

Chapter 6 - Tombstone Teri

Chapter 7 - The Holy Redeemer Lonely Hearts Club

Chapter 8 - A Mourner

Chapter 9 - War Is Declared

Chapter 10 - The Motorcycle

Chapter 11 - Suspended

Chapter 12 - The Harbor

Chapter 13 - Bad News Betty

Learn more about the book, click Here.

Or you can read my memoir, The Promise, or the Pros and Cons of Talking with God, published by TouchPoint Press, which deals heavily with my suicidal college days:

Sample Chapters:

Prologue - My Mother

Chapter 1 - RestingPlace.com

Chapter 2 - Elisabetta

Chapter 3 - The Upload

Chapter 4 - The Kobayashi Maru

Chapter 5 - Gina

Chapter 6 - Tombstone Teri

Chapter 7 - The Holy Redeemer Lonely Hearts Club

Chapter 8 - A Mourner

Chapter 9 - War Is Declared

Chapter 10 - The Motorcycle

Chapter 11 - Suspended

Chapter 12 - The Harbor

Chapter 13 - Bad News Betty

Or you can read my memoir, The Promise, or the Pros and Cons of Talking with God, published by TouchPoint Press, which deals heavily with my suicidal college days:

No comments:

Post a Comment