Hidden Secrets, the original DVD artwork

It's not too far of a stretch to say that "Hidden Secrets," my second produced feature, was born partially out of my frustration with the independent film business as experienced through "21 Eyes." At least as far as I am concerned.

If you've been following this blog, you know that I feel that, financially-speaking, the film business is hopelessly skewed in favor of the distributors. It was frustrating to know that if we could only sell 5000 or so DVDs of "21 Eyes" ourselves online at the suggested retail price of $19.95 our investors would be made whole. And that should be the goal, kiddies: Making the investors whole. A happy investor will help you make more movies. An unhappy investor will have you checking your caller ID every time before you answer the phone. You don't want that. Life's too short.

But how do you sell 5000 copies of your DVD?

Sounds like it should be easy. You set up a webpage. Easy enough. You set up a purchase fulfillment mechanism. Easy enough. You get tens of thousands of potential buyers to your website. Not so easy.

Once, I remember talking to a producer who told me you always had to ask yourself: "Who will want to watch your movie?" I have rarely heard wiser words in this business. If you don't know who will want to watch your movie, maybe you shouldn't make it.

Who would want to watch "21 Eyes?"

We designed the film for young, hip filmgoers. The people who went to independent film festivals. People who wanted to see something new. Something that would challenge them. These people, however, were not the people who would line up to buy the film at Walmart. That's a problem if you want to make money. In fact, I can say, based on the comments from viewers on various webpages, that the average filmgoer who is simply looking for ninety minutes of escapism has had little patience for our film. People love it or hate it. There's no middle ground on "21 Eyes."

So how do we find our audience? Where do they gather? Where can we hand out a few copies to get word of mouth going?

If you know, tell us. Even if you're the "Gone With The Wind" of voyeuristic, security-camera tape whodunit mysteries, you'll have a hard time getting potential buyers to your site. It takes a great deal of work or an unbelievable amount of luck to get something to go "viral." It takes more than a little word of mouth unless your website contains footage you took with your cellphone of a drunken Lindsey Lohan stripping at a nightclub. Come to think of it, you need more than that today. We've all seen that. What you need is advertising. And, if you have an indie mystery, where do you advertise your film to get the ball rolling? It's not like there's a natural constituency for such films.

If we had a low-budget horror film, we could put banner ads on websites like Fangoria. We could buy tables at horror conventions and sell copies directly to the fans. Of course, if we had a horror film, we would also be competing with 9000 other films that were made on a shoestring. So, despite having a more easily-defined market, it is incredibly difficult for a horror film to gain any real attention. It is even more difficult for an oddball, non-linear mystery.

Now, if Rebecca Mader had gotten the "Lost" gig just as we were finishing post-production, we might've been able to pull something off, but, sadly, timing didn't work in our favor.

We weren't going to be able to sell 5000 copies of the film off our webpage. We had to put ourselves in the hands of a distributor. And I'm not sure he had washed them.

This left me at a career crossroads. My agent was dead. Should I write a new mainstream script and use it to get a new agent and try for the conventional brass ring again? Or should I try to write and produce another low budget independent movie? Having learned that it was more fun to write movies than scripts, I decided to continue playing around in the independent world. But before I did, I wanted to answer the question: "Who will want to watch your movie?"

One thing was certain. I wasn't going to self-produce and promote a horror film, as much as I enjoy the genre. Too much competition. Too many desperate filmmakers giving their films away essentially for nothing. Even the local success stories didn't hold up to scrutiny.

Here's about as good as it gets. You find an investor who gives you $30,000. You spend the money responsibly and actually make a good film. So good that Lion's Gate or The Asylum gives you an advance of $30,000 for it. Yippee. You can pay back your investor in full. You can hold your head up high. You don't have to spend the next five years ducking his phone calls. You are a success. Except for one problem: You don't have any money. The investor rightfully got all of the advance. You're hoping to get paid on a percentage of the sales, but, guess what, you never see those percentages. Why? Because the distributor will keep increasing his costs so that the film never becomes profitable. Or he simply won't pay you. So, in the end, you've worked a year or two or three for free. Even if you got to pocket the whole advance, it's probably less than what you're making at your day job.

Plus, unless the film gets you a financed-production deal with a distributor, chances are you are going to be starting at zero again when it comes time to make your next film.

Depressed yet? I was.

I wanted to write a film I could believe in with a built-in market that could readily and inexpensively be reached via advertising. The answer: The faith-based market.

Starting with the success of 1999's "The Omega Code," the Christian film market began to expand. However, the mainstream media didn't start to notice the trend until the phenomenal success of Mel Gibson's "The Passion of the Christ." Still, they were able to dismiss the genre's viability. After all, Mel Gibson was a big star. His presence, even behind the camera, made The Passion a success. Then came the little independent film "Facing The Giants." No stars. No production values. Just high school football and Jesus, and not particularly in that order.

That was the answer. I would write and produce a quality, low-budget faith-based film.

I would write a script that I could produce for about $100,000 with an additional $50,000 for advertising and promotion. I would set up a booth at the Christian Booksellers convention and follow-up with direct marketing, both internet and mail. I would buy banner ads on various webpages and hold some money back for spots on Christian radio stations in key markets.

I could do this. And without any cynicism.

I was a believer since high school, albeit as a Roman Catholic. (Oh no, I've accidently outed myself. I might never be able to work in the faith-based field again!) I had the faith. I had the heart. I had the language. I could easily write a faith-affirming film that would entertain as well as enlighten. In fact, I already had.

Yours truly in his First Communion gear.

The first scripts I sent to Hollywood had strong Biblical themes. And, oddly enough, they were well-received. Back then, there was no real faith-based genre. The agents looked at the scripts as stories, and they thought the stories worked. The second script I wrote was an Apocalyptic thriller called "The Mark." At the time, I was working with an agent who didn't represent writers. He did, however, represent directors, and he wanted to try to set the script up somewhere with one of his clients. The agent, now a television and feature producer, was Jewish. He wasn't put off by the Christian material at all. He took the script as a powerful Rod Serling-ish metaphor about The Holocaust. If anything, he thought it was too Jewish and he didn't want to be perceived as being too pushy about his faith.

Nothing happened, and I didn't care. Back then I was writing a new script every couple of months so I didn't place much of an attachment on any particular one. However, in retrospect, I wish I would have pursued that script. I would have hit the "Left Behind" market years before those books. Drat. (Then again, it was an early effort. Too sloppy and too long. But I would be happy to revisit it if anyone was interested!)

My third script, a horror film called "Then The Judgement," was even more Christian than the previous one. In fact, it has a stronger evangelical message than some of the straightforward faith-based films I have subsequently written. And you know what? Nobody complained. Why? Because it wasn't propaganda. The spiritual themes of the story were essential to this tale of good and evil and the possibility of redemption. People often raise their eyebrows when I say I really want to write horror films, but, think about it, horror is the only "mainstream" genre where it is acceptable to delve into supernatural and spiritual themes.

(Pardon me if I don't give you the log-lines of these films but they are very high-concept and still viable. I don't want them stolen. That happens. And its happened to me.)

The first person to represent Then The Judgement was an East Coast entertainment lawyer. Well, technically-speaking, she didn't represent me or the script. There is a legal distinction between what a lawyer is supposed to do and what an agent is supposed to do. Lawyers are not supposed to hawk scripts. She told me she could only represent me in negotiations if someone wanted to buy the script. That said, she did, inadvertently I suppose, send the script around to a few places to see if someone wanted to be on the other side of these projected negotiations. She was the first person to get me a really cool rejection letter. From Paramount. On their stationary! I had it hanging on my wall for years.

After a while, my lawyer said her firm wouldn't let her send scripts around anymore. I had to find a real agent. By then, of course, I had a new script I wanted to sell too. It was a secular light drama which will remain nameless here. I decided to simultaneously pitch "Then The Judgement" and The Light Drama. I sent out ten letters per script to agents every two weeks. I got interest in both scripts almost immediately. (Little did I know it at the time, but this was the height of the spec script market.)

A major agent at CAA, through his assistant, requested to read "Then The Judgement." I'd tell you who the agent was, but you wouldn't believe me. And, perhaps more importantly, if you did believe me, you'd think I was a total idiot. (He's still there and very powerful.) Stu Robinson, from the boutique, writer-oriented agency, Robinson, Weintraub and Gross, requested The Light Drama. I heard back from both of them in about a week. I got a letter from the CAA agent's assistant. He liked "Then The Judgement," but he requested three changes. Those changes seemed large at the time, but they were nothing compared to the changes I make on commissioned scripts nowadays. The next day I got a call from Stu Robinson at 9am EST. Yes. He was calling me at 6am his time! I was impressed. I mean, I wasn't even awake. He woke me up! He liked The Light Drama very much. He wanted to represent it. And he was the guy who sold "E.T". And he represented John Sayles. You can't go wrong with that!

I told Stu my dilemma. How CAA was interested in "Then The Judgement." He asked me to send him the script. He read it. He liked it. However, he said it would be a mistake to make my first sale a horror film. I would be typecast as a horror writer. He said I would be much better off selling The Light Drama first. That was the kind of script that would get me commissioned work, and that's where the money is. He made a good case, and I decided to go with him. And, anyway, CAA wanted changes. Forget them! (Ah, the cockiness of youth.)

I'll leave it to another blog to examine whether that was the right choice!

Seanie Goes To Hollywood

Hidden Secrets, Revealed, Part 1, Pre-History

Hidden Secrets, Revealed, Part 2, First Contact

Hidden Secrets, Revealed, Part 3, The Writing

Hidden Secrets, Revealed, Part 4, Production

Read about the making of my other features:

Other Faith Based Writing Blogs:

Building The Faith Based Ghetto

Building The Faith Based Ghetto

Do Christian Creators Know When Their Movies Are Bad?

God Told Me To Write It

Enter The Haters

Zach Lawrence and the End Times Quandary

God Told Me To Write It

Enter The Haters

Zach Lawrence and the End Times Quandary

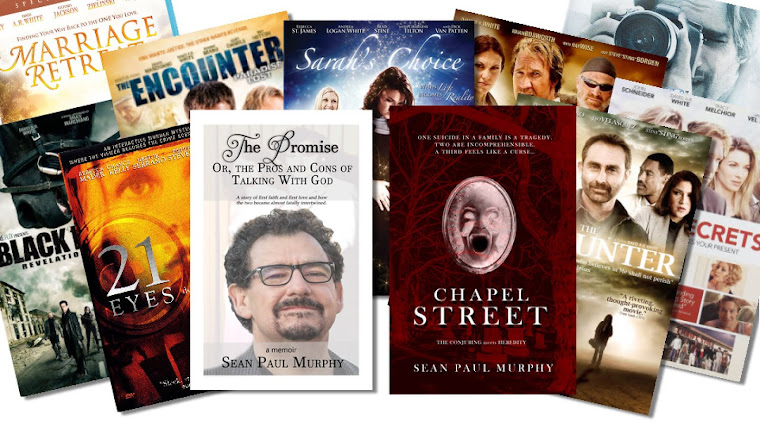

Be sure to check out my memoir The Promise, or the Pros and Cons of Talking with God, published by TouchPoint Press. It is my true story of first faith and first love and how the two became almost fatally intertwined.

Here are some sample chapters of The Promise:

Be sure to check out my novel Chapel Street. It tells the story of a young man straddling the line between sanity and madness while battling a demonic entity that has driven his family members to suicide for generations. It was inspired by an actual haunting my family experienced.

You can buy the Kindle and paperback at Amazon and the Nook, paperback and hardcover at Barnes & Noble.

Listen to me read some chapters here:

Read about the true haunting that inspired the novel here:

Follow me on Twitter: SeanPaulMurphy

Follow me on Facebook: Sean Paul Murphy

Follow me on Instagram: Sean Paul Murphy

Subscribe on YouTube: Sean Paul Murphy